Q. When is a convenient time to deal with distractions on the flight deck?

A. There isn’t one—that’s why they’re called “distractions.”

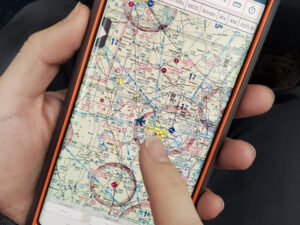

From passengers talking loudly to trying to figure out how to use your favorite electronic flight bag app, pilots constantly encounter distractions. Recognizing that they can be dealt with in a methodical way and prioritizing safety are paramount to ensuring you and your passengers, arrive at your destination. Even a brief distraction can be a link in an accident chain that has disastrous results.

From passengers talking loudly to trying to figure out how to use your favorite electronic flight bag app, pilots constantly encounter distractions. Recognizing that they can be dealt with in a methodical way and prioritizing safety are paramount to ensuring you and your passengers, arrive at your destination. Even a brief distraction can be a link in an accident chain that has disastrous results.

According to the FAA, a distraction is “anything that reduces our focus on successfully completing the task at hand.” Distractions can be classified into three broad categories:

- Communication: For example, having non-pertinent conversations with passengers during the final approach.

- Head-down time: For example, spending too much time looking at checklists or charts and failing to scan for traffic or landmarks.

- Dealing with anomalies: For example, responding to an abnormal or unexpected situation.

We might not be able to prevent interruptions, but we can be intentional about minimizing their effect.

Lets look at each of these categories in detail.

Communication

“Sterile cockpit” is a term most commonly used by airline pilots and refers to a rule that prohibits non-pertinent conversations below 10,000 ft (14 CFR Sec. 121.542, 135.100). The rule originated from an accident at Charlotte Douglas International Airport in North Carolina in 1974 that resulted in 72 fatalities.

“Sterile cockpit” is a term most commonly used by airline pilots and refers to a rule that prohibits non-pertinent conversations below 10,000 ft (14 CFR Sec. 121.542, 135.100). The rule originated from an accident at Charlotte Douglas International Airport in North Carolina in 1974 that resulted in 72 fatalities.

Eastern Airlines Flight 212 was flying into dense fog when the airplane crashed 3 miles short of Runway 36 due to Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT). The NTSB report found that the pilots engaged in unnecessary conversations involving “politics and used cars” during the approach phase of flight. The report stated that the flight crew lacked “altitude awareness at critical points during the approach due to poor cockpit discipline.”

The FAA published the Sterile Cockpit Rule in 1981.

Although not legally applicable to Part 91 non-commercial operations, it is highly recommended that all pilots adapt the rule to general aviation flights. Even if we’re not flying for business, we should all be professionals. Hopefully, you’ve already set personal minimums for factors like weather, but have you taken the time to set a “sterile cockpit altitude?” Maintaining a sterile cockpit at 2,000 ft. AGL for local flight and 5,000 ft. AGL for flight outside the vicinity of your airport is a reasonable touching-off point, but set yours to whatever you are comfortable with and make sure you inform your passengers of your sterile cockpit rule during the passenger briefing.

Don’t assume your passengers know what that means. To them, “sterile cockpit” could be interpreted as you just want to keep things clean in the cabin. Passengers can easily get caught up in the adventure of a flight. Let them know that there should be no unnecessary conversations or questions below your altitude threshold unless it is an emergency. Passengers often forget about the rule, especially on long taxi routes, so it may be necessary to remind them every so often. But you could always get them involved by asking them to help look for other traffic.

Additionally, you should never be afraid to tell your check instructor or DPE about the rule. On checkrides, you are responsible for safety, not the examiner. Unless you are under the hood, it’s your job to see and avoid. Remember – Aviate, Navigate, Communicate, and Manage (or “mitigate” if you need a rhyme). Your examiner might ask a non-pertinent question while you are on a 1-mile final to throw you off. Be prepared to respond confidently and say, “Let’s talk about it on the ground.”

Additionally, you should never be afraid to tell your check instructor or DPE about the rule. On checkrides, you are responsible for safety, not the examiner. Unless you are under the hood, it’s your job to see and avoid. Remember – Aviate, Navigate, Communicate, and Manage (or “mitigate” if you need a rhyme). Your examiner might ask a non-pertinent question while you are on a 1-mile final to throw you off. Be prepared to respond confidently and say, “Let’s talk about it on the ground.”

Hint: Use the pilot or crew isolate function on your intercom to separate your communications from the passengers. It essentially turns your intercom into separate systems so you don’t have to hear distracting conversations.

Heads-down time

It is always important to refer to checklists and charts to verify that your aircraft is set up correctly for each phase of flight. Always remember to fly the airplane first (aviate). Sometimes you can get so caught up with one part of a task that everything else gets tuned out, but it’s important to learn to recognize when you’re getting tunnel-vision. For example, if you’re practicing instrument approaches, don’t fixate on the approach plate while the aircraft begins to deviate.

Don’t rely on your instructor either. Not because they aren’t capable of helping, but because they will likely let you get off track so you can see the effect of the distractions first-hand. Your CFI may be sitting silently next to you, leading you to believe that everything is going just fine, while you drift from your desired heading. Your passengers won’t know any better. It’s up to you to divide your attention inside and out. By the time you look outside or scan your instruments, you may have already made a 180-degree turn and find yourself flying opposite to the approach course.

Don’t rely on your instructor either. Not because they aren’t capable of helping, but because they will likely let you get off track so you can see the effect of the distractions first-hand. Your CFI may be sitting silently next to you, leading you to believe that everything is going just fine, while you drift from your desired heading. Your passengers won’t know any better. It’s up to you to divide your attention inside and out. By the time you look outside or scan your instruments, you may have already made a 180-degree turn and find yourself flying opposite to the approach course.

According to the FAA, at least 90 percent of the pilot’s attention should be devoted to outside visual references and scanning for airborne traffic. In instrument conditions, 90 percent of that time should be spent on scanning and interpreting your instruments. Focusing too much time on secondary tasks like briefing an approach plate or completing a checklist is a distraction that could set you up for disaster. Stay ahead of the plane by setting up your navigation well in advance. Verify your navigation is set properly before following the magic magenta line.

Dealing with anomalies

It takes hours to carefully plan a cross-country flight. We all hope everything goes exactly according to plan, but often, flight conditions change or systems don’t work as expected. Be prepared to resolve any abnormal conditions, just don’t let your focus drift away from actually flying the airplane.

Eastern Air Lines Flight 401 departed New York’s JFK airport and was on the approach course for Miami International in 1972. The flight was went according to plan until the landing gear was lowered for the approach. The First Officer noticed that the landing gear indicator light was not illuminated. The pilots cycled the landing gear up and down, but failed to get the “gear down and locked” confirmation. The cockpit crew were so fixated on rectifying the gear indication that the Captain dispatched the Second Officer to the avionics bay for a look. The pilot’s thought the autopilot was on, but the altitude hold was inadvertently disengaged. The aircraft began a descent so gradual it could not be perceived by the crew. 101 people perished when the aircraft eventually crashed into the Florida Everglades.

It was reported later that the landing gear functioned correctly and the indicator lights were just burnt-out. Was Eastern Air Lines Flight 401 brought down by a burnt out light bulb? No. The crew’s fixation on the landing gear indicator distracted them and they forgot to do the most important thing—fly the plane!

Managing Distractions

No matter what your experience level is, every pilot is going to experience distractions. Learn from the mistakes of others to manage distractions with the following tips:

- You may have control over some distractions but not others.

- Be intentional. The actions under your control, including standard operating procedures and checklists, should be conducted during periods with low task saturation.

- Make sure that passengers understand your need to focus on the flight. Tell them when it is acceptable to engage in conversation and/or use the pilot/crew isolate function on your intercom.

- Keep communications clear and concise. Getting straight to the point will save you time for other important tasks.

Recognize when you get distracted, then make it a priority to re-establish situational awareness:

- Identify: What was I doing?

- Ask: Where was I interrupted or distracted?

- Decide/act: What decision or action shall I take to get “back on track?”

There is no excuse for allowing yourself to become distracted with any tasks that take your attention away from flying the airplane. This behavior is unprofessional. According to the FAA, “a problem still exists in the aviation industry with some pilots acting unprofessionally and not adhering to standard operating procedures, including the sterile flight deck rule.” These behaviors were cited in accidents reports including Pinnacle Airlines flight 3701 (October 14, 2004) and Colgan Air, Inc. flight 3407 (February 12, 2009). Regulations have been drafted to deal with the problem and lead to safer skies. Changes to professional pilot training are being implemented that includes operations familiarization and leadership/mentoring programs for new hires.

No matter what you fly, you can do you part to increase safety by making a few slight changes in how you manage your flight deck. From mitigating unnecessary communications to dealing with unplanned circumstances, we can all improve by recognizing and eliminating bad habits.

Check out the Gleim Safe Pilot Course (SPC). It is a recurrent ground training course designed to increase pilots’ knowledge and abilities in regard to operating safely in the National Airspace System. SPC covers various aircraft accidents and highlights the causes of and lessons to be learned from them. Practical guidance on creating an emergency action plan is also a main aspect of this course. The course is only $29.95, or you can preview a short version of the course for free.

Check out the Gleim Safe Pilot Course (SPC). It is a recurrent ground training course designed to increase pilots’ knowledge and abilities in regard to operating safely in the National Airspace System. SPC covers various aircraft accidents and highlights the causes of and lessons to be learned from them. Practical guidance on creating an emergency action plan is also a main aspect of this course. The course is only $29.95, or you can preview a short version of the course for free.

Written by: Ryan Jeff (AGI, Aviation Research Assistant) and Paul Duty (CFI, CFII, MEI, AGI, Chief Instructor)