There are four basic types of fronts, each with its own distinct weather characteristics. Understanding the differences can help pilots gauge how soon weather changes will occur and when inclement weather may arrive, dissipate, or increase in severity. This blog explains the four basic fronts that exist within our atmosphere.

There are four basic types of fronts, each with its own distinct weather characteristics. Understanding the differences can help pilots gauge how soon weather changes will occur and when inclement weather may arrive, dissipate, or increase in severity. This blog explains the four basic fronts that exist within our atmosphere.

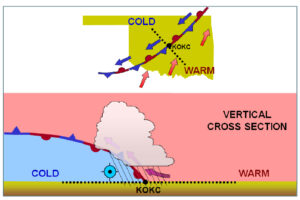

Warm Front

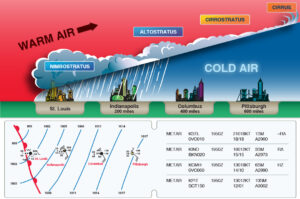

Warm fronts are boundaries of slow-moving air masses that replace masses of colder air ahead of them. Warm fronts typically travel between 10 and 25 miles per hour and contain warm, humid air. As the warm air is lifted, the temperature drops and condensation occurs, forming clouds.

Warm fronts typically have a gentle slope, so the warm air rising along the frontal surface is gradual. An indication of an approaching warm front is the formation of cirriform or stratiform clouds, along with fog, ahead of the frontal boundary. Cumulonimbus clouds often form in the summer months when the potential for an unstable lapse rate is high. Recall that the three ingredients for thunderstorms to form are sufficient moisture, an unstable lapse rate, and lifting action. A warm air mass often includes the first two ingredients, and the lifting action is caused by warm air flowing over the cooler air ahead of the front, as depicted in the figure above.

Warm fronts typically have a gentle slope, so the warm air rising along the frontal surface is gradual. An indication of an approaching warm front is the formation of cirriform or stratiform clouds, along with fog, ahead of the frontal boundary. Cumulonimbus clouds often form in the summer months when the potential for an unstable lapse rate is high. Recall that the three ingredients for thunderstorms to form are sufficient moisture, an unstable lapse rate, and lifting action. A warm air mass often includes the first two ingredients, and the lifting action is caused by warm air flowing over the cooler air ahead of the front, as depicted in the figure above.

Light to moderate precipitation in the form of rain, sleet, snow, or drizzle often occurs, along with poor visibility. Since warm air is less dense than cold air, the barometric pressure first falls, rises slightly, and then continues to fall until the warm front passes completely.

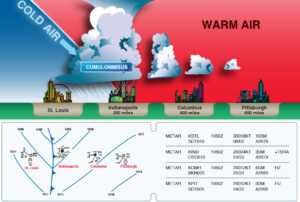

Cold Front

Cold fronts, on the other hand, travel more rapidly than warm fronts, at a rate of 25 to 30 miles per hour (potentially up to 60 miles per hour). Cold fronts are dense masses of air that remain close to the ground and displace warmer air by sliding under it. The ascending air rapidly decreases in temperature, forming clouds.

Cold fronts, on the other hand, travel more rapidly than warm fronts, at a rate of 25 to 30 miles per hour (potentially up to 60 miles per hour). Cold fronts are dense masses of air that remain close to the ground and displace warmer air by sliding under it. The ascending air rapidly decreases in temperature, forming clouds.

Ahead of a cold front, cirriform, towering cumulus clouds, and cumulonimbus clouds may form. Severe weather is more common during a cold front passage and may include rapid development of heavy rain showers, lightning, hail, and/or tornadoes. Eventually, good visibility prevails once the cold air dominates the area. Temperatures remain cooler, and because cold air is more dense, the barometric pressure continues to rise.

Certain cold fronts may be fast-moving fronts, and the friction between the ground and the cold front creates a steeper frontal surface, forming a narrow band of weather concentrated along the leading edge of the front. In light of this, a continuous line of thunderstorms, or squall line, may form along or ahead of the front. Squall lines are a serious hazard to pilots, as squall-type thunderstorms can extend well above the capability of many airplanes and can extend in a line stretching 300 to 500 miles, making them difficult to navigate around. As such, flying through a line of thunderstorms or a squall line should be avoided. Flight over the top of or around squall lines is usually not an option. However, since they are fast-moving, waiting them out usually does not take very long.

In a stationary front, the forces of the two air masses are relatively equal; neither air mass is replacing the other, and the boundary can remain stationary. The weather associated with a stationary front is typically a mixture of weather from warm and cold fronts. Pilots can expect the weather in the area to persist for several days, and the surface winds will blow parallel to the frontal zone.

Occluded Front

An occluded front occurs when a fast-moving cold front catches up with a slower warm front. It may benefit you to think of an occluded front as three sections – a cold front, a warm front, and an area of cool air ahead of the warm front.

An occluded front occurs when a fast-moving cold front catches up with a slower warm front. It may benefit you to think of an occluded front as three sections – a cold front, a warm front, and an area of cool air ahead of the warm front.

A cold front occlusion occurs when the fast-moving cold front is colder than the air ahead of the slow-moving warm front, resulting in the warm front being lifted aloft into the atmosphere. This collision of different air masses produces a mixture of weather found in both warm and cold fronts.

Conversely, a warm front occlusion occurs when the air ahead of the slow-moving warm front is colder than air from the cold front. When this happens, the cold front will be lifted above the area of cool air ahead of the warm front, causing severe weather with a relatively unstable lapse rate. In such situations, embedded thunderstorms, rain, and fog are likely to occur.

What Can I Do With This Information?

By understanding the different characteristics of fronts, you can make more informed flight planning decisions. For example, we understand that cold fronts are fast approaching with little warning, and they bring about a complete weather change in just a few hours. With this knowledge, analyzing a surface analysis chart may favor delaying an intended flight until the front completely passes. If the weather is caused by a stationary or occluded front, it may be best to delay your departure, since those fronts could take several days before the weather becomes conducive to completing your flight.

By understanding the different characteristics of fronts, you can make more informed flight planning decisions. For example, we understand that cold fronts are fast approaching with little warning, and they bring about a complete weather change in just a few hours. With this knowledge, analyzing a surface analysis chart may favor delaying an intended flight until the front completely passes. If the weather is caused by a stationary or occluded front, it may be best to delay your departure, since those fronts could take several days before the weather becomes conducive to completing your flight.

Always obtain a weather briefing before each flight. If you are unsure of the characteristics or effects of an approaching front, a weather briefer can help you understand the impending weather phenomena and associated hazards.

To learn more about fronts and weather systems, reference the Gleim Aviation Weather and Weather Services book!

Written by: Ryan Jeff, Aviation Research Assistant