On 8 Dec 2014, a corporate jet carrying one pilot and two passengers crashed into a house in Montgomery County, Maryland, tragically killing all three occupants and a mother and two children on the ground. The NTSB reported that the aircraft encountered clouds and was exposed to structural icing conditions while descending to their destination. They noted that there were numerous reports of ice from pilots flying in the area, and the jet pilot was still in the clouds almost 15 minutes after entering them. With its flaps extended and landing gear down on final approach, the jet should have been flying at 104 knots, however the cockpit data recorder showed it was flying at 87 knots in the final moments before the stall.

On 8 Dec 2014, a corporate jet carrying one pilot and two passengers crashed into a house in Montgomery County, Maryland, tragically killing all three occupants and a mother and two children on the ground. The NTSB reported that the aircraft encountered clouds and was exposed to structural icing conditions while descending to their destination. They noted that there were numerous reports of ice from pilots flying in the area, and the jet pilot was still in the clouds almost 15 minutes after entering them. With its flaps extended and landing gear down on final approach, the jet should have been flying at 104 knots, however the cockpit data recorder showed it was flying at 87 knots in the final moments before the stall.

Although this winter accident is alarming, flying during the cold season should not be intimidating. It isn’t any riskier than flying in the summer, as long as pilots exercise good judgment and are aware of the hazards associated with this season. Regardless of whether you spend the winter months flying in Florida or Alaska, each season should change how you prepare for your flights. Here are some tips on how to prepare both the aircraft and yourself to operate in colder weather.

Although this winter accident is alarming, flying during the cold season should not be intimidating. It isn’t any riskier than flying in the summer, as long as pilots exercise good judgment and are aware of the hazards associated with this season. Regardless of whether you spend the winter months flying in Florida or Alaska, each season should change how you prepare for your flights. Here are some tips on how to prepare both the aircraft and yourself to operate in colder weather.

Preparation

Check your oil

In the winter, engines typically require less viscous oil that is able to withstand the harsh cold. With a lower viscosity, the oil is better able to circulate within the engine after engine start.As such, it is imperative that you refer to the aircraft manual for oil weights and change the oil accordingly.

In the winter, engines typically require less viscous oil that is able to withstand the harsh cold. With a lower viscosity, the oil is better able to circulate within the engine after engine start.As such, it is imperative that you refer to the aircraft manual for oil weights and change the oil accordingly.

Clear your Engine breather tubes

In the cold, the engine breather tube may be blocked due to liquid condensation freezing in the lines. The engine breather tube is a vent that allows the engine to get rid of water vapor and liquid water during operation. A blocked breather tube can pressurize the engine and cause seals to fail. Failed seals can cause oil leaks, eventually causing engine failure. It is important that you clear the breather tube before and after each flight.

Check for carbon monoxide leaks

It is likely that you will reach for the cabin heat when flying in cold weather. However, in aircraft equipped with a heat exchanger that surroundsthe muffler or other parts of the exhaust system, there is a danger of carbon monoxide seeping into the cabin. Critically inspect the cabin heat system for cracks, replace parts that seem unreliable, and install a carbon monoxide detector on the flight deck.

Inspect hoses, clamps, hydraulic fittings and seals

Hose lines and tubes eventually degrade which could lead to an engine malfunction. The harsh cold could exacerbate deteriorating lines, fittings, and seals so it is best to inspect them as winter approaches.Refer to the appropriate aircraft maintenance manual and torque all damps and fittings to cold weather specifications. If you are unsure what constitutes preventive maintenance, refer to 14 CFR part 43 or consult with your certificated mechanic.

Colder temperatures causes air to contract

Be sure to check the pressure in the tires and struts as colder temperatures can cause pressure to decrease dramatically. While doing so, be sure to inspect the seals on the aircraft’s oleo struts to ensure they have not deteriorated.

Clear before start, cover after shutdown

For aircraft parked outside, it is good practice to cover the wings and cowling to prevent ice build-up between flights. If unable, take special care during preflight to ensure that the wings are free of ice (including frost) and the engine is not blocked or clogged before considering flying. Use a broom to brush of any snow or ice on the wing as they could significantly reduce lift, increase drag, and increase takeoff, approach, and stall speeds. Icing is a serious hazard and should not be neglected.

For aircraft parked outside, it is good practice to cover the wings and cowling to prevent ice build-up between flights. If unable, take special care during preflight to ensure that the wings are free of ice (including frost) and the engine is not blocked or clogged before considering flying. Use a broom to brush of any snow or ice on the wing as they could significantly reduce lift, increase drag, and increase takeoff, approach, and stall speeds. Icing is a serious hazard and should not be neglected.

Operations

Prime thoroughly, but correctly

Some aircraft may have specific limitations for cold weather operations. To ensure the engine is started correctly, refer to the Cold Start instructions in the aircraft manual. Doing so does not just ensure correct engine operation, but also preserves its life. Incorrectly starting the engine without priming and allowing the engine to heat up can cause significant internal damage.

Be patient, allow the engine to warm up

The engine will require more time to warm up in the cold. Be patient and allow the engine temperatures to rise to acceptable limits before departing. The aircraft manual will have the appropriate RPM to set the engine to during this warm-up. It is especially critical to know the nuances between difference aircraft that you fly. You may operate an aircraft with a Lycoming or Continental engine that requires a warm up RPM of 1,000 to 1,200, however, Rotax engine may require 1,800 to 2,000 RPM. Examine the oil pressure and temperature indications during this process and ensure you do not exceed the limits. Under no circumstances should you depart until the engine has sufficiently warmed-up.

Watch for icing conditions

Known icing conditions exist when visible moisture or high relative humidity combines with temperatures near or below freezing. Supercooled Liquid Droplets, or SLDs, play a significant role in aircraft icing and flying through SLDs will almost guarantee ice accretion on the aircraft. Accumulated ice can create excessive weight, cause uncommanded rolls, greatly increase drag, and destroy lift – causing stalls. Icing can also block pitot tubes and inhibit radio communications and navigation equipment When inadvertently caught in icing conditions, immediately change altitude. Remember that freezing rain means that warmer temperatures are above you. Or find an altitude where liquid precipitation is no longer a factor contributing to ice accumulation. An altitude change of at least 3,000 or more may be necessary to clear icing hazards.

Known icing conditions exist when visible moisture or high relative humidity combines with temperatures near or below freezing. Supercooled Liquid Droplets, or SLDs, play a significant role in aircraft icing and flying through SLDs will almost guarantee ice accretion on the aircraft. Accumulated ice can create excessive weight, cause uncommanded rolls, greatly increase drag, and destroy lift – causing stalls. Icing can also block pitot tubes and inhibit radio communications and navigation equipment When inadvertently caught in icing conditions, immediately change altitude. Remember that freezing rain means that warmer temperatures are above you. Or find an altitude where liquid precipitation is no longer a factor contributing to ice accumulation. An altitude change of at least 3,000 or more may be necessary to clear icing hazards.

Avoid abrupt control movements when icing is suspected

Airplanes that have collected ice will stall at higher-than-published stall speeds due to effect of drag and altered airfoil shape. As such, avoid abrupt control movements, make small pitch corrections, and keep your bank angles shallow, which minimized load factors and allows a greater margin of safety before stalling.

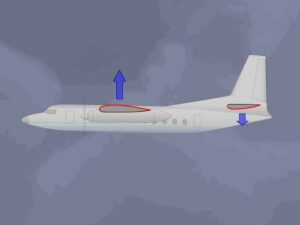

Understand “tailplane stalls”

Tailplane stalls caused by icing is a serious and extremely dangerous threat. Tailplane stalls can happen suddenly as the surface is often outside of the pilot’s visual range. Recall that airplane wings generate lift upward. The tailplane, on the other hand generates negative lift (downward lift). Therefore, recovery in a suspected tailplane stall is to climb, not descend – climbing will in fact lower the angle of attack of the tailplane.

Tailplane stalls caused by icing is a serious and extremely dangerous threat. Tailplane stalls can happen suddenly as the surface is often outside of the pilot’s visual range. Recall that airplane wings generate lift upward. The tailplane, on the other hand generates negative lift (downward lift). Therefore, recovery in a suspected tailplane stall is to climb, not descend – climbing will in fact lower the angle of attack of the tailplane.

Some indicators of tailplane icing, and subsequent tailplane stall are elevator oscillations or vibrations, abnormal nose-down trim change, reduction or loss of elevator effectiveness, and sudden uncommanded nose-down pitch.

A tailplane stall due to ice accumulation is most likely to occur during the extension of the flaps to the landing position. Thus, tailplane stalls due to icing are mostly likely during the approach and landing phase of flight.

To recover from a tailplane stall, you should pitch up, retract the flaps to the last safe position and increase power only to the extent that you compensate for the loss of lift created from retracting the flaps. A tailplane stall condition may tend to worsen with increased airspeed and increased power settings at the same flap setting.

Always be prepared to hand-fly

If you encounter icing on approach to landing, turn off the autopilot. The autopilot can prevent you from detecting the onset of a stall or handling problem. Remember that autopilot systems cannot compensate for the effects of icing. A blocked pitot tube will provide incorrect readings to the computer, and the autopilot will not adjust stall speed according to the amount of icing accumulated. Overreliance on the autopilot can force the aircraft into a stall.

Go easy on crosswinds

When landing on a icy runway with less than perfect braking conditions and indirect wind, you should lower your max crosswind component for a safe landing. A commonly used rule of thumb is to lower the aircraft’s demonstrated crosswind component in half for a snow dusted runway, and cut it by 75% for ice landings. This will help prevent the aircraft from weathervaning and skidding into the wind.

Be light on the brakes

In cold conditions, the ground surfaces may be slippery, and abruptly braking can cause the aircraft to slide across the surface. While excessive use of brakes can causes them to heat up, potentially melting snow or ice, the moisture could refreeze within the brakes, and landing gear causing them to lock up.

In cold conditions, the ground surfaces may be slippery, and abruptly braking can cause the aircraft to slide across the surface. While excessive use of brakes can causes them to heat up, potentially melting snow or ice, the moisture could refreeze within the brakes, and landing gear causing them to lock up.

Flying in the cold has its challenges; however, risks can be managed when pilots exercise good judgment and are aware of the hazards. Before you fly this winter, take some time to educate yourself on the hazards of icing and cold weather operations by reviewing the Gleim Aviation Weather And Weather Services book, Study Unit 13.

Written by: Ryan Jeff, Aviation Research Assistant