Inadvertent stalls are are an example and loss of control in-flight (LOC-I) and are a leading cause of fatal general aviation accidents. Many accidents involving stalls are caused by simple distractions. These accidents wouldn’t have occurred if the distractions had been avoided. The number of accidents could be further reduced by using proper technique to recover from a stall when one occurs. Inadvertent stalls are stressful situations, so the procedure must be drilled until it is mastered.

There are two basic operations pilots use to practice stall recovery:

- Power-off stalls replicate and help us avoid a stall during an approach to landing.

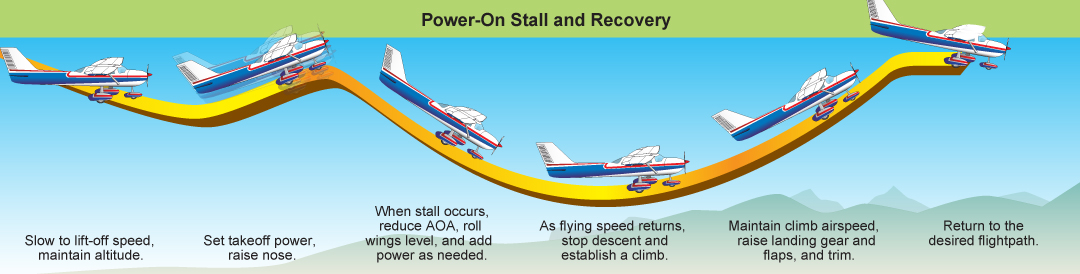

- Power-on stalls, also known as departure stalls, replicate and help us avoid a stall immediately after taking off.

Practicing these builds awareness of the factors that can lead to or compound the severity of a stall. The earlier a potential stall is recognized, the easier it is to correct. LOC-I incidents are commonly caused by uncoordinated flight, equipment malfunctions, pilot complacency, distractions, turbulence, and poor risk management, such as inadvertent flight into IMC. Note: Many instructors use planned distractions when teaching stalls.

Stall Recovery

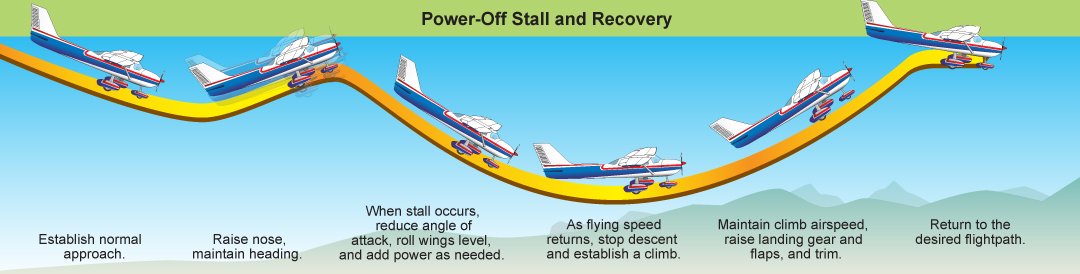

The signs of an imminent stall include decreased control effectiveness and the presence of a stall warning indicator. When you realize you have entered a stall, the first, most important step to begin recovering is to reduce your angle of attack. Most training airplanes require at least 4 steps to fully recover from a stall.

- Pitch nose-down to decrease the angle of attack.

- Reduce the bank by leveling the wings.

- Add power as needed.

- Return to the desired flight path.

Complex or advanced airplanes, such as those with retractable landing gear, autopilot, or spoilers, require additional steps depending on their configuration. Stall recovery should always be performed according to your airplane’s AFM/POH.

Power-off Stalls

Students often, mistakenly,increase pitch aggressively to induce a power-off stall. When entering a stall,you should increase the pitch slowly and smoothly up to a landing pitch attitude, approximately 10° nose up, and hold it there until the stall occurs. The recovery should not be aggressive. If the airplane is loaded properly within its CG range, the nose should naturally lower when a stall occurs.

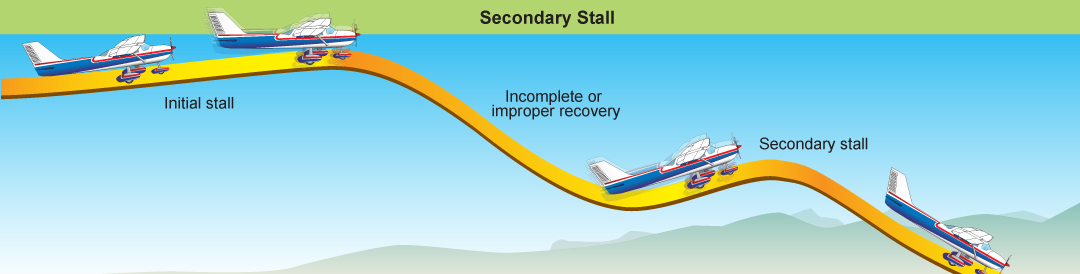

Instead of shoving the yoke forward, lower the angle of attack by simply releasing the back pressure and adding a little forward pressure if needed. This will result in a quicker recovery, and less altitude will be lost because this technique prevents the airspeed from greatly increasing, as it would in a dive. You should then return to the entry altitude by climbing at the best rate (VY). If you pitch up too aggressively, you may inadvertently enter a secondary stall.

We should feel confident in our ability to recognize the signs of imminent stalls to safely recover from one before it becomes fully developed.

When practicing power-off stalls, don’t wait too long to lower the flaps while decelerating. If you do, then by the time the flaps have been set, the airspeed may have already decreased past the approach speed you want to maintain during a stabilized descent. To avoid becoming unstabalized during approach, configure the airplane as soon as possible to give yourself plenty of time to set up for the maneuver.

Take a moment to view the power-off stall video demonstration below. First, notice how the pilot picks a clear outside visual reference to maintain his heading. Be aware of your turning tendencies and correct them with rudder input, keeping the visual reference straight ahead. Notice how the recovery is not a dive. All that is necessary to “break the stall” is a minor dip in pitch attitude before immediately pitching for VY attitude.

Power-On Stalls

To enter a power-on stall, you should smoothly and quickly increase the pitch to between 20° and 25°. According to the Airman Certification Standards, you should “transition smoothly from the takeoff or departure attitude to the pitch attitude that will induce a stall.” Once the pitch has been increased sufficiently, do not let the nose drop until the stall occurs. Students often pitch up initially, but let the nose drop as the airspeed decreases, which will not induce a proper power-on stall. In order to hold the same pitch attitude, you need to steadily increase the back-pressure as the elevator loses authority. If you let the nose drop too early, you may never reach a full stall, or if a stall does occur, you may not get a clean break and recovery will be more difficult.

Be aware of the need to keep your airplane in coordinated flight (i.e., the ball centered), even if the controls feel crossed. If a power-on stall is not properly coordinated, one wing will often drop before the other wing and the nose will yaw in the direction of the low wing during the stall. Because the airspeed is decreasing with a high power setting and a high angle of attack, the effect of torque becomes more prominent. Right rudder pressure must be used to counteract this torque. Failure to maintain coordinated flight can result in a spin.

In Summary

Although student pilots repeatedly practice stalls in the course of their training, they remain a significant source of General Aviation fatalities. As pilots, we should feel confident in our ability to recognize the signs of imminent stalls to safely recover from one before it becomes fully developed. If you have yet to reach that level of confidence, go fly with an instructor until you do. If you are already confident, recognize that stall accidents can still happen to the best of us and that we should never become complacent.

Although student pilots repeatedly practice stalls in the course of their training, they remain a significant source of General Aviation fatalities. As pilots, we should feel confident in our ability to recognize the signs of imminent stalls to safely recover from one before it becomes fully developed. If you have yet to reach that level of confidence, go fly with an instructor until you do. If you are already confident, recognize that stall accidents can still happen to the best of us and that we should never become complacent.

To learn more about the flight maneuvers required to become a private pilot, check out the Gleim Flight Maneuvers and Practical Test Prep. These books provide step-by-step instructions for all flight maneuvers required for to train for your certificate in accordance with the FAA Airman Certification Standards, plus a complete discussion of the common errors for each maneuver.

Written by Karl Winters (CFI, CFII, AGI), Gleim Aviation Editor and Assistant Chief Instructor